Languages

- NL

- EN

Emmy Andriesse, Germaine Richier, 1953,

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

‘I am more moved by the trunk of a dead tree than by an apple tree in full blossom.’

Germaine Richier (Grans 1902 - Montpellier 1959) was one of the most important sculptors working in France in the aftermath of the Second World War. Her works reflect that period in a most lyrical fashion. The rough, scarred, hollowed and bleeding surfaces of her sculptures, her half-human, half-animal figures speak of the existential fear and dilemma brought about by the experience of the war. Richier’s art was likewise shaped by a childhood spent in Provence in close proximity to nature, by Surrealist and Existentialist notions popular in her circles, by the experience of being both a woman and a sculptor, and by a creative spirit drawn to experimentation and to the fantastical.

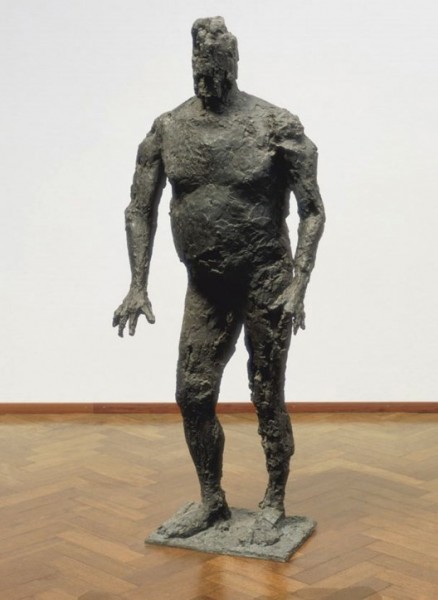

In 1953, the Surrealist writer André Pieyre de Mandiargues described Richier as a ‘force of nature’ for her violent treatment of her material. He emphasized, however, that hers was an energy ‘bringing forth goodness’. Works such as Storm Man (L’Orage, 1947) are a testimony to that. Though scarred and weathered, the figure appears to be moving forward. There is destruction, but there is also the hope of survival and regeneration. This duality is one characteristic of Richier’s art.

Germaine Richier, L’Orage (Storm Man), 1947,

Bronze, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

Richier’s art forms part of a tradition of representing the human figure in bronze. She studied sculpture under Antoine Bourdelle, who, in turn, was the pupil of Auguste Rodin. While many of her contemporaries turned to abstraction as a response to the war, Richier both remained faithful to the figure and transformed it. Before 1939, she created more realistic portrait busts and female nudes. During and after the war, her artistic world became populated with metamorphosing, fantastical creatures: a woman with the limbs of an insect, a horse with six heads, a man of the forest with imprints from leaves on his body. The figures are still human, but their humanity is so fragile, so precarious. They are expressive of a post-war psyche which is torn, wounded and animalistic, yet intent on survival and rebirth.

Richier’s creativity also extended to the techniques she used. Her early, classical works are experiments in form. Later, she achieved expressivity by various means. She made use of natural materials such as branches or stones before casting the sculptures in bronze. She introduced zig-zagging wires into some of the works to suggest entrapment. Her surfaces are often hollowed and cracked, as if in decay. In the 1950s, Richier started using colored pieces of glass or asked painters to paint backdrops for her sculptures. These have been seen to anticipate Pop and Nouveau Realisme.

Richier’s name was well-known to the Dutch public during her lifetime. She exhibited on her own in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1955 and 1959, as well as participating in several group exhibitions. After her death, however, her works were only displayed sporadically.

The exhibition is organized in collaboration with Musée Picasso in Antibes, where Richier's work will be on display before traveling to museum Beelden aan Zee. This will be the first significant showing of Richier’s art in the Netherlands since 1959, and thus offers a chance to rediscover an oeuvre which is as captivating as it is disturbing.