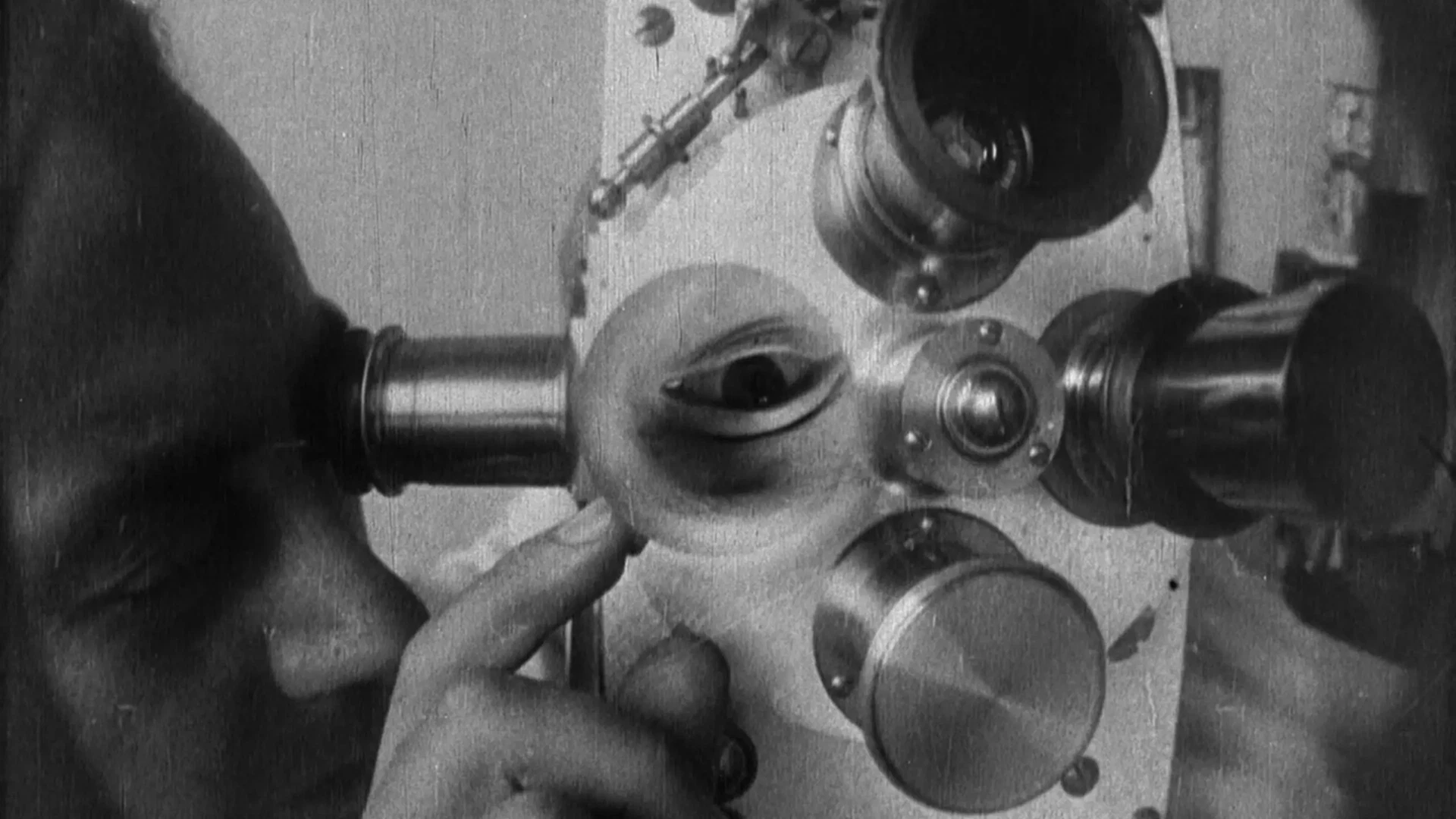

Just as he created his photographs and artworks by bringing together extremes, he applied the same principle to his films. The mechanism through which films are made—the camera itself—is sometimes present within the film. The question of reality and the registration of the world around us—can this notion be considered valid for film and photography? Man Ray instead reveals the underlying mechanisms and processes of filmmaking.

Man Ray also employs camera-less techniques, such as rayography. Although the resulting images may appear unreal, they are in fact traces of objects on light-sensitive material, such as a strip of film scattered with objects and then exposed to light. The human body is presented as a projection surface onto which images are cast, allowing multiple images to be recorded simultaneously. Negative imagery and double exposure—Man Ray shies away from nothing in order to make his films as expressive and distinctive as possible.

In this way, an atmosphere of ghosts and shadow worlds is evoked: a realm that is never fully visible. Filming through frosted glass or textile gauze creates obscurity, blurring, and a sense of the unknowable. In other words, the viewer is invited to fill in the gaps, to participate intellectually, and to complete the suggestion.

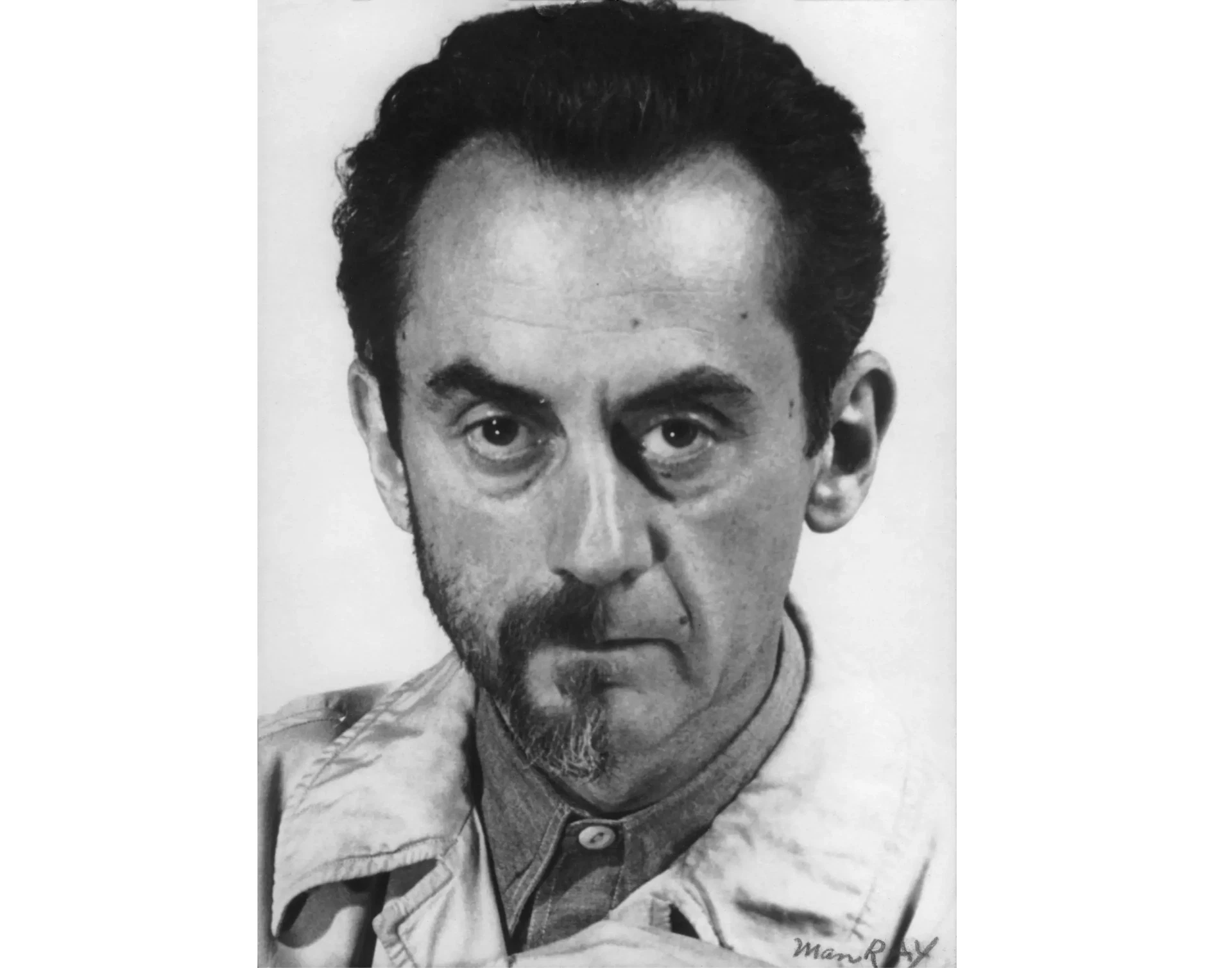

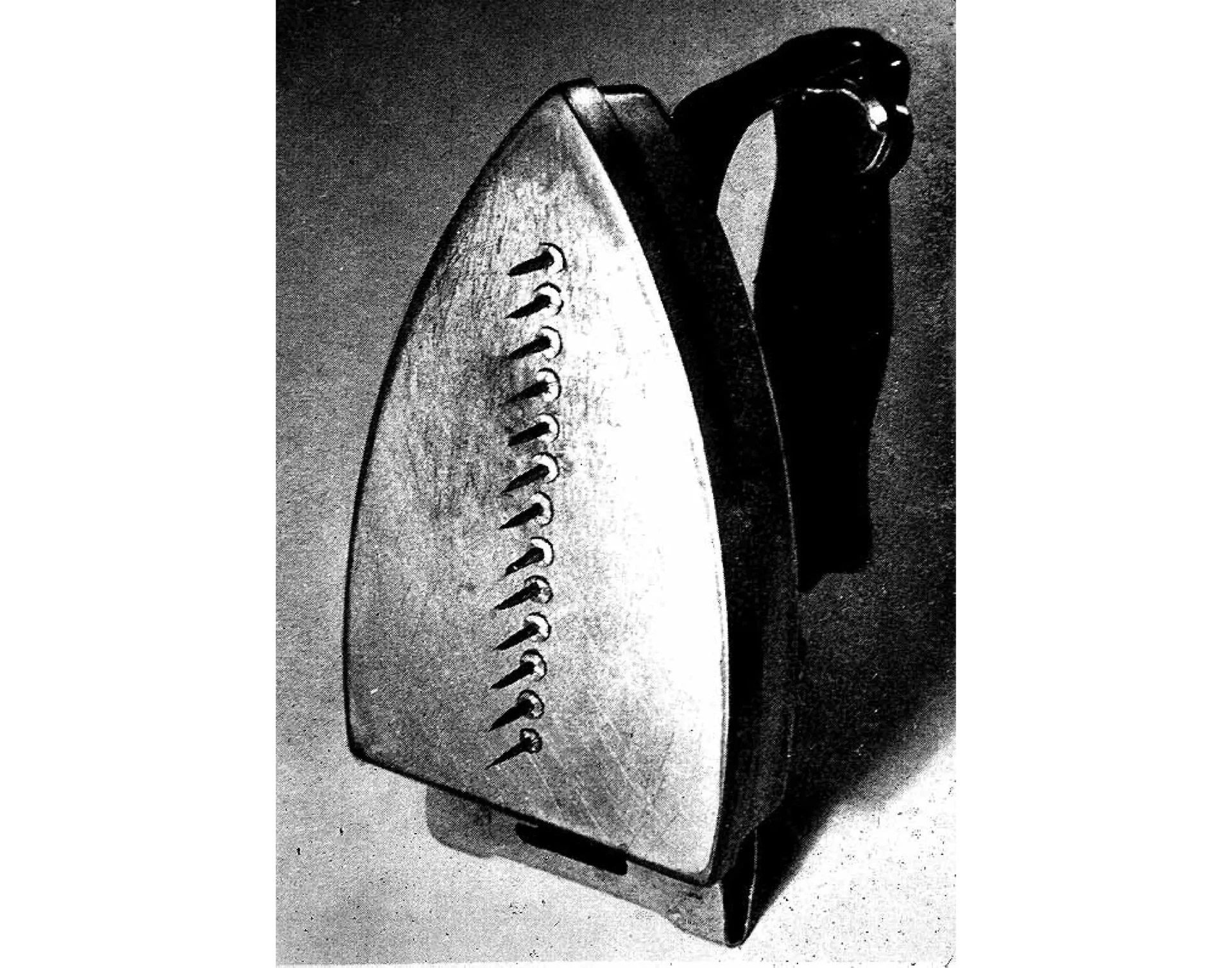

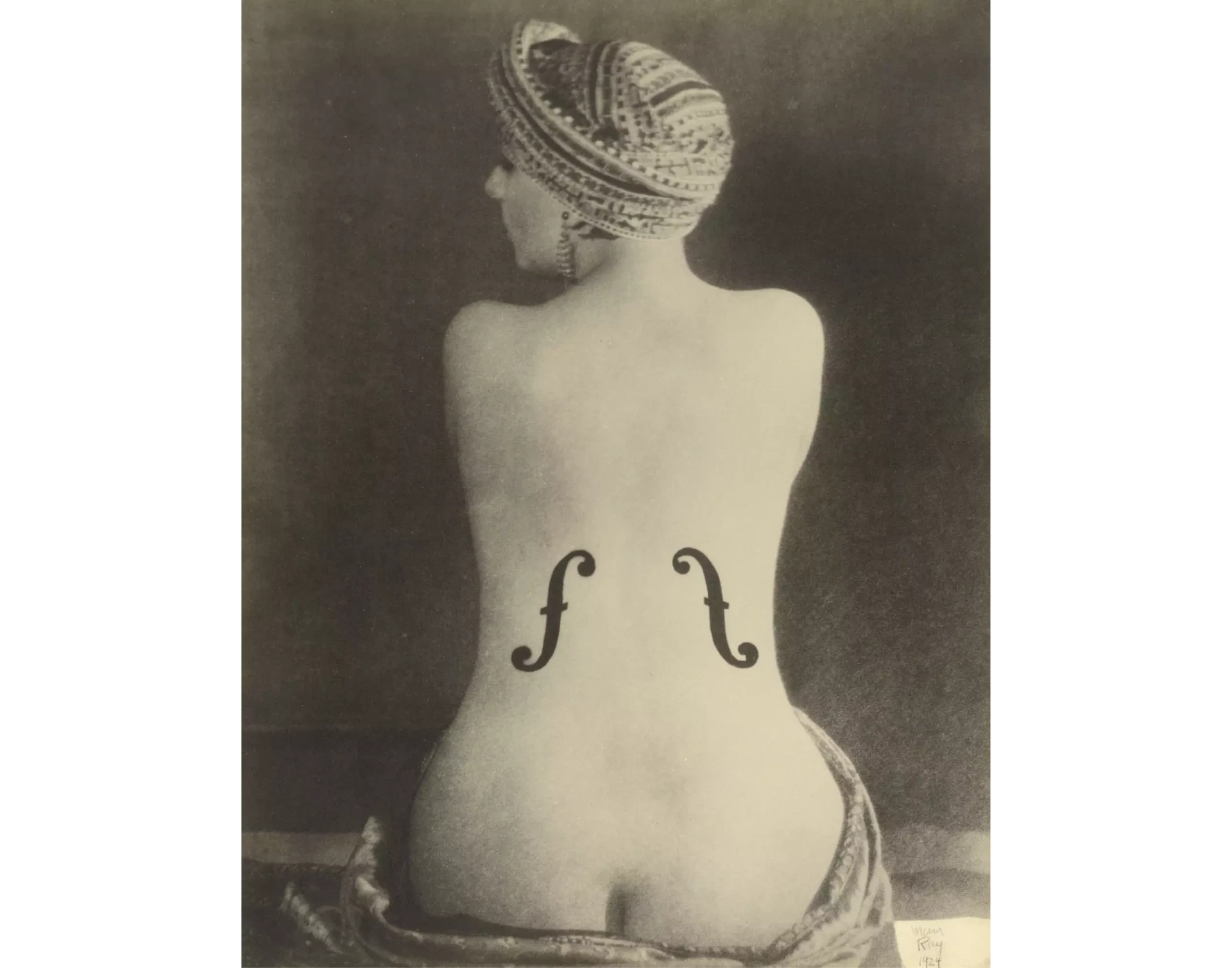

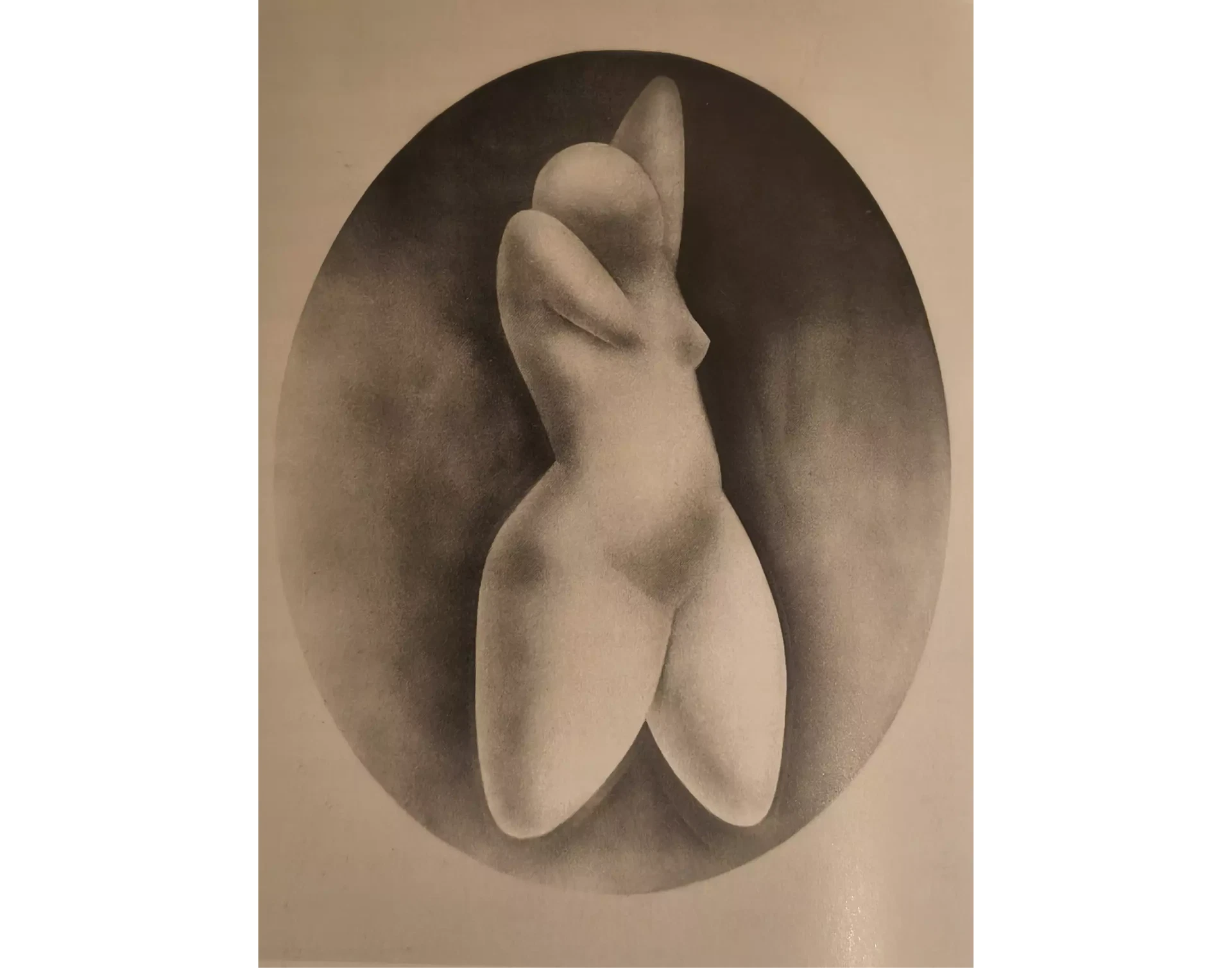

Man Ray is the creator of a complex visual world that has an artificial quality. He is not content with merely observing everyday reality; instead, he transforms it through the many interventions he employs. He is an artist of extremes, which he unites within a single work of art. This dialectic—the synthesis of everything that moves within him and within us—is what he seeks to express, sometimes without fully knowing what he is doing, or by allowing his subconscious to speak.

Reference list

1. (Knowles 2012, page 77) “Un côté avec barbe pour ceux qui préféraient avec. Un côté sans, pour ceux qui préféraient sans”.

2. Man Ray appears as a character in the 2025 VRT series about Surrealism, framed as an entertaining but entirely fictional murder mystery.” This is not a murder mystery: https://www.vrt.be/vrtmax/artikels/2025/10/22/wie-is-man-ray-in-this-is-not-a-murder-mystery/

3. Based on Britannica Online; Britannica Academic, s.v. ‘Man Ray,’ accessed December 22, 2025, https://academic-eb-com.leidenuniv.idm.oclc.org/levels/collegiate/article/Man-Ray/62816.

4. Catel & Jose-Luis Bocquet, Kiki de Montparnasse, London, Self Made Hero, 2022. A graphic novel about the life of Kiki.

5. https://www.cultureelerfgoed.nl/actueel/weblogs/kunstwerk-van-de-maand/2023/de-rug-van-kiki-man-ray-1924

6. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/kiki-de-montparnasse-man-ray-biography-2238009

7. Mark Braude, Kiki Man Ray. Art, Love and Rivalry in 1920s Paris, New York, Norton, 2022.

8. In Bourgeade, Pierre, Bonsoir, Man Ray. Montroughe, France, Fondation Maeght, 2002.

9. Fotiade, Ramona. ‘Spectres of Dada: From Man Ray to Marker and Godard’. In Dada and Beyond, Volume 2, 89-106. BRILL, 2012.